The Deserters

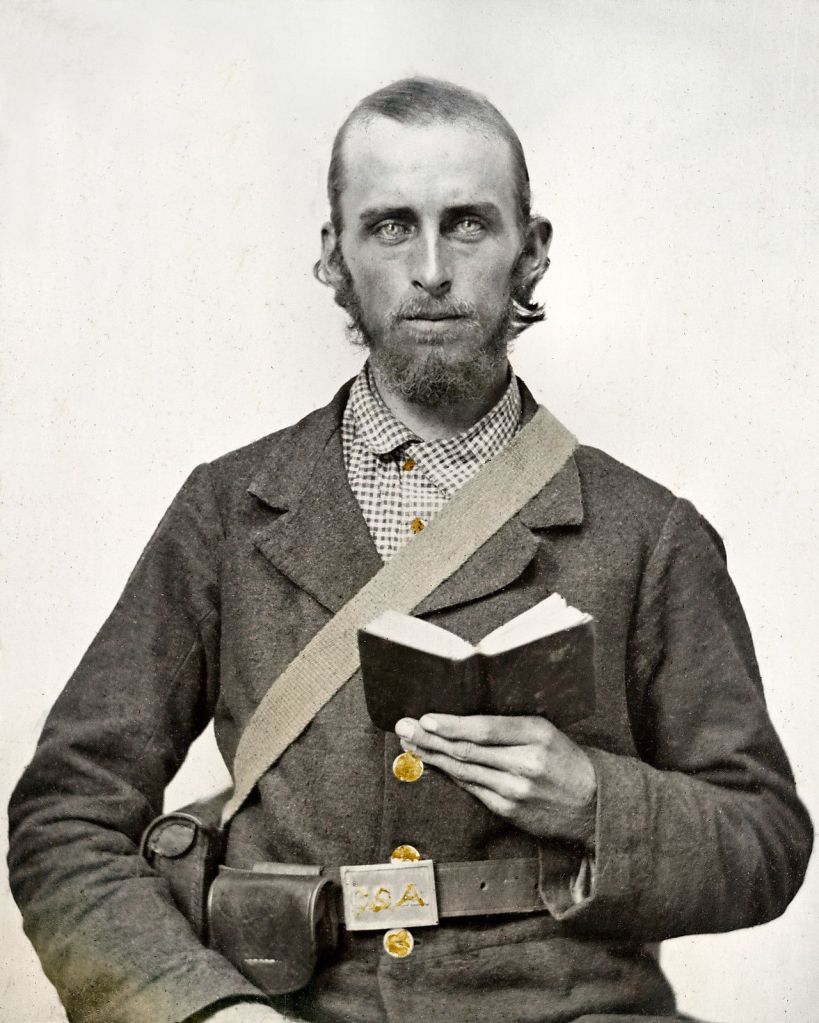

Colliers, West Virginia

1863

John and Tom marched ahead of Ben and Joe. Turning off the main road into a muddy pockholed corn field they stumbled under the weight of their packs and weaponry. The men had returned from battle only a few months prior. Returned to devastated farms and lean families. They tried to remember the habits of their former selves, but physical and psychological ailments changed them. If they thought the company of family and friends would remind them, they found strangers there too. John was prone to meanness before he had left to fight. He had itched to shoot a few men and he did, killed more than his share. Perhaps more than the others he had been afraid. And now he spent his days drinking and telling war stories to whoever would listen, mostly old men down at the tavern. Tom came back a shadow of himself. He had lost forty pounds, his eyes gaunt with haunted expression. Alone on his small farm, his days and evenings were spent on his porch watching the weeds grow with not much on his mind. Once opinionated on various topics, mostly farming and politics, his mind recorded not ideas, but vague feelings of tiredness, hunger, and thirst. Ben was the kindest of the men and possibly the most damaged. He slipped back into the Ben of old without anyone noticing the holes and scars that riddled his insides. Joe was the strongest. When he saw his run down farm he looked out on his land and thought, Virginia will once again be a beautiful country. He tilled his fields and the sweat that rolled down his brow was his own for his own. And seeing the dark rows of rich soil, he planted wheat. In the fall he had harvested the grain and delivered it to the miller, selling the surplus and taking home what he would need for the winter. And then the orders arrived. They were to march south toward Napier. Packing food, water, blankets, wintercoats, and ammunition they said goodbye to their families. They marched until dark and made camp under a grove of oak trees. They rolled out their beds and sat in the dark nibbling hard tack and salted pork. They listened and spoke in hushed tones.

“I thought we done our part.” John now preferred the tavern, regular meals, and a warm bed. Ben and Tom eyed each other with grim, resigned expressions. They slept huddled together through the cold night. In the icy pre-dawn they boiled coffee and then set out. They would hike 15 to 20 miles per day. Depending on the terrain and weather they’d make Napier in eight days or so. It started to rain. They stopped to unpack their overcoats. Their brogans, or Jefferson boots, were starting to take on water.

“Hey, there’s that coal mine not far. Why don’t we stop, get dried up?” John said.

The coal mine had been abandoned two years earlier. None of the men replied, but as they neared the location they all turned towards it. Entering the mine it was dark and damp. The men lit an oil lamp and made their way deeper seeking a dry spot. A rumble started deep in the mountain above. The men straightened, hitting their heads. Stones tumbled behind them. They ran from the falling rumble. After the air cleared, they inspected the fall.

“These boulders are too heavy.” Ben said, trying to move several.

“Could there be an exit?” John asked.

“Unlikely, but we have to check.” Joe started down into the mine.

The others tested the rocks. Not one budged. They sat and waited for Joe to return.

“Nothing. It ends 100 feet in.”

“What about using a musket to leverage the stones?” John said.

The muskets were 56” of wrought iron steel and incredibly strong. Joe picked up one of the muskets and went to the blockage. John joined him. They started near the ceiling trying the rock. Nothing. They worked down. Not the slightest movement. The stones were too large and heavy. The men sat around the lamp. They were tired and scared. The mine walls were stone, so digging out wasn’t possible.

“We need to conserve. Dump your bags. Let’s see what we have.” Joe said

The men spilled the contents of their bags. Soldiers often collected food along the way and they had only brought enough food for a couple of days. There was coffee, salted pork, hardtack, beef jerky, and beans. They each had a canteen of water and oil for burning. The first night none of the men slept. If not for Joe’s watch time would have been impossible to track. They called out into the rubble and kept looking for weak spots.

“What if we use our gun powder, try to blast through?”

“That’s an idea John. How much powder we got?” Joe asked.

The men gathered the black powder together.

“The best place is up high. If we can blast a small opening we might be

able to leverage some of the rock, maybe squeeze through.” Joe said.

The men agreed that the top where the stones were thinner and the weight pressing down wasn’t as great was the best blasting location. Ben cut a strip out of a cotton shirt and cut rows into it to make a longer strand. He made several of those and tied them together. He repeated that with three more shirts making about 30 feet of wick. Ben dipped the strip in oil. Joe set the powder with the oil soaked strand spooled out. The others were already well back. He lit the fuse and ran. The blast shook the mine, clouds of black powder filled the space. The men coughed and breathed through whatever material they had. When the gunpowder and dust cleared the men went to the cave in. The rock had cracked. They used their muskets to try and leverage the stones loose. They were able to remove some of the rubble but there was no gap. A solid wall of immovable stone remained.

“That was all of our powder.” John said.

“It barely made a dent.” Joe said.

The air in the cave felt thinner now, but the men didn’t mention it. They had thought the black powder would work and were starting to feel desperate. They agreed that they would take turns tapping on the rock in case someone happened by. The mine sloped down into the earth, so to dig out from any point that wasn’t near the entrance seemed insurmountable. They searched the walls for weak spots, roots or soil, but there was only blasted and chiseled rock. They sat in a dry spot. Each man knew that fear must be checked. They had witnessed how fear could consume a person like wildfire. To comfort spirits, Joe told the story of Rip Van Winkle while they nibbled jerky. They conserved their energy now, using less oxygen, needing less food. Joe counted the hours and days with his watch. In the frenzy of that first day, he thought another may have passed without his noticing. And now the men asked him the hour and the day. Waiting. Acknowledging it was death they waited for. The men ate and drank once per day. On the fifth day they ran out of food and water. There were pools of water in the cave. A man could go a long time without food. They had witnessed that too. The meanness in John began showing. He had hidden food he stole from Tom and Ben. To hearten the men Joe told stories. Ben asked if he remembered scripture. Joe spoke several uplifting verses he hoped would ease Ben’s spirit. John seethed and paced. When he had finished the stolen food, madness raged. Insanity that had laid in wait emerged, expressing itself in ways others would feel. Joe didn’t know it, but they were twelve days in. They had spent four days searching for a way out, trying to move rocks. Their situation seemed hopeless. Joe began writing notes with the paper and pencil he had brought to write home with. Guilt overwhelmed him. He should be on the battlefield with his neighbors and countrymen. In his heart, he knew that he had turned into this mine, had followed John, to delay their journey south. And fate had weighed his cowardly soul. He wouldn’t hide now. If his body was ever found, people would know why they were here in this abandoned mine. He would be judged without turning out lies. The truth would be told.

November 3, 1863

Should this ever reach the outside world, let it be known that we are prisoners here, owing to the cave in of the mine. We are deserters and were hiding here when the mine caved in. Food and water are all gone. We are doomed as no one outside is aware of our whereabouts. This is about the eighth day of our imprisonment.

John paced. The men were afraid to shut their eyes. They had all killed before. Men were capable in lesser circumstances and now they distrusted each other. Joe stopped telling stories as it brought the murderous glare of John. The men had gone this long without food before. There was something about being trapped in the dark that made it unbearable. Perhaps it was the knowledge that they were going to die there in that tomb. Maybe it was the dark after all. Men starving in prisons had been more humane. A dead man’s hand was unfolding and there was no way to bluff their way out. The lack of oxygen intensified the nightmare running through their minds. John had fed his psychosis and now it spilled over, could no longer be contained. Tom seemed more ghost than man. Being already thin, he was skeletal. His spirit seemed to have already left him. He followed John like someone lost.

November 4

John Ewing and Tom Ackleson have killed Ben Ayers: are eating him. I have already eaten my boot leg. The water in the mine is terrible. Our oil is getting scarce; air becoming foul. I only know the day of the month by my watch.

Joe didn’t know if he could have stopped it. He knew John was raving mad. With the quickness of a cat he leapt onto Ben and stabbed him. John and Tom bit into his still pulsing flesh and ate. Joe had seen horrors, was hardened by war. He looked away, his stomach sick. He thought of their decision to turn into this mine. It hadn’t felt like a decision. It was an action, a hand guiding them. And now he wondered if they were here for John. Perhaps this was John’s fate and to spare the innocent they too were sacrificed. He had seen men driven to lunacy, outrage and slaughter women, children, and the elderly. Joe wondered if these thoughts were to ease his own guilt. He examined his conscience. Ben lay there full of flesh, but John didn’t have enough. If this were hell he was reveling in it. Joe kept his eyes open and prayed. He spoke to his family. He would not die with human flesh on his lips.

November 6

Ewing has just killed Ackleson. Cut off one of his feet and is eating it, dancingaround and flourishing his dirk knife like a maniac.

Ewing was covered in blood. His had eyes lost all humanity before he killed Ben, but Joe was sure he saw the devil in them now. Ewing lunged at Joe. The will to survive is great. People will cling to the smallest thread, the slimmest of hope. Joe fought for his life knowing that it may only be a life of days. Alone. In the dark. Dying of starvation. His thoughts were very clear now. Joe had experienced intensified clarity and self reflection. Perhaps it was the ease of taking a step into the afterlife. His final hours would be thought filled. He would not be tortured though he had suffered. He fought for those final hours.

November 7

I am alone now with the dead. I had to kill Ewing in self defense. I have just eaten my other boot-leg. Am sleepy. Good bye. I enclose this note in this flask to preserve it if possible. So that ever found, our sad fate will be known.

Joseph Obney

The notes by Joe in italics are reprinted from the Pioche Record. February 27, 1896.

The skeletons along with Joe’s notes were discovered 32 years after the four men’s deaths. The men were remembered in the town and thought to have died in battle. While the dates, names, and places are real, the story is entirely fictional.

The Widow

Alice Jones sat on her porch at her typewriter. A tear rolled down her cheek. She looked up at the desert, her inspiration, and patted her eyes with a handkerchief. She remembered when she first came to this place from New York. She was recently widowed and on impulse…was it impulse? No, it was a decision to live, to feel. She hopped the train to Nevada. She had purchased a piece of land before moving. It was 80 miles north of Reno with several springs, some being hot springs. The realtor had said it was good range land for cattle. She had hired M J Curtis, an architect and builder, on recommendation. She wasn’t too particular, so their correspondence was agreeable. She wanted something unassuming and not too large. The one feature that was required was a large covered porch with a fireplace. Mr Curtis tried to dissuade her from the outdoor fireplace saying it would attract all manner of rodent and wild animal, but she had insisted. She trusted Mr Curtis as an architect to have a good eye and knowledge to consider light, wind, and whatever else one considered when building to choose the location for the home. Mr Curtis hired an interior designer to select the furnishings with instructions that it be humble, comfortable, and western. A light touch here and there with something special like a rug or her bedding was acceptable. She needed a lot of bookshelves so the walls didn’t need decoration. If there were to be art, she wanted it from a local artist, nothing pompous or pretentious. When she arrived in Reno she had only four large trunks to be shipped to her new home. There had been China, art, and fine furnishings but she didn’t have an heir. She gave everything except a few sentimental items, clothing, and her collection of books to her husband’s younger brother William. She remembered the trip to her new home. She took the stage part of the way. Mr Curtis had met her where the stage turned west. They stayed on the McOrmie’s place. Mr Curtis had stopped at their homestead several times during the construction of Mrs Jones home. He always brought supplies or treats, anything he thought they might need. Mrs McOrmie was a kind and generous host. Alice remembered the most delicious biscuits and gravy she had ever eaten. Mrs McOrmie offered her own bed, but Mr Curtis had set up a cot for her in the main room and one for himself in their barn. Mrs McOrmie had breakfast and coffee ready before Alice had woken up. Mr Curtis got their horses ready. He had suggested a buggy, but Alice had insisted. She was an experienced equestrian and had always dreamt of riding a Mustang. They thanked the McOrmie’s and headed towards Alice’s new home.

“What do you think of the desert country Mrs Jones?”

“It’s beyond my expectation Mr Curtis. I must say I am overwhelmed by the

wonderful bouquet of sage. I’m surprised that it isn’t written about more.

Perhaps one gets accustomed to it as ocean dwellers do the scent of the sea.”

The stage had brought Mrs Jones two thirds of the way and so they had a full day of riding ahead of them with rests. Mr Jones had brought four strong Mustangs.

“Can you see it Mrs Jones. Your home?”

Alice could see a white house in the distance on a small rise. When they arrived Mr Jones handed the horses to one of his workmen to take care of.

“Ling has dinner ready for us.”

The porch was just as she imagined. They went inside and dinner was being set in front of four men. They stood when Alice entered. She immediately admired the antler chandelier that hung above the table.

“This is Mrs Jones.”

The men said hello. Alice told them to sit and eat before their food got cold. The workmen had spent the day moving in furniture and touching up final details before Mrs Jones arrived. Mr Curtis pulled a chair out at the head of the table for Alice and he sat at the other end. Ling brought out two more plates.

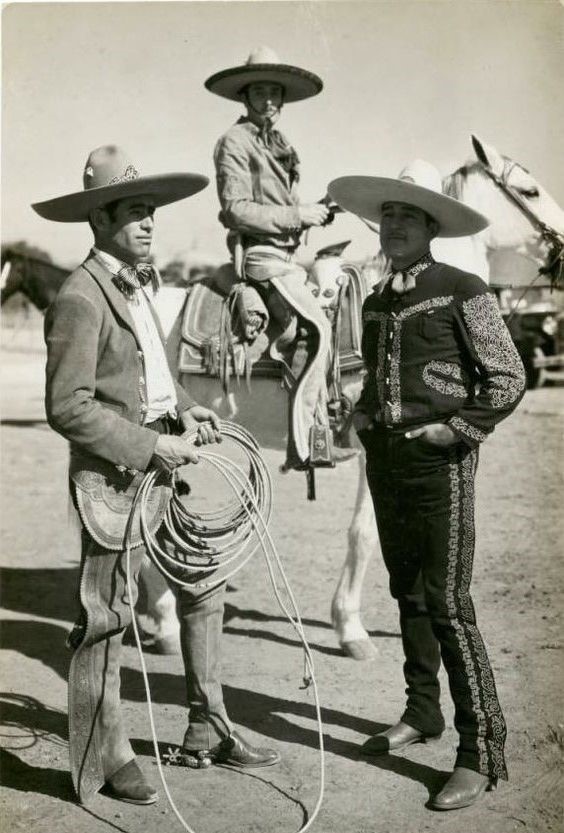

“What do you plan to do with the property Mrs Jones, raise cattle.”

“I’m afraid not. I was told that it is ideal country for that purpose. I’m going to write Mr Curtis. I’ve always wanted to write a novel, set in the west with the vaquero as the hero.”

“Fascinating. I believe it would be a big hit back east.”

“Perhaps. That does not concern me. I just want to accomplish the task. It is inside me and I must get it out. Do you understand Mr Curtis.”

“I believe I have an idea. Sometimes, designing a building, something draws me in a direction that is outside of my intellectual directive. Perhaps it is an artistic force.”

“Indeed Mr Curtis. I believe you understand.”

“Will you miss the city Mrs Jones?” One of the workmen asked.

“I will not. Do not misunderstand me. I loved my life there with my husband, but that is gone now. I spent much of my time reading and dreaming of this wonderful country. No. I shan’t miss the city at all, Mr?”

“Jim. Jim ma’am!”

“Jim. And what about you? How do you feel about this place?”

“Well ma’am. I came over from Missouri in ‘49. Weren’t for no gold. I guess I was same as you. When I set eyes, I just knew I’d be buried here.” Alice nodded.

“Are you afraid of Injuns Mrs Jones?” Jim asked.

“People keep asking me that question. It has not crossed my mind in the least. In my experience people are afraid when they do not understand something. Perhaps I will learn, as some have said to me with dishonest intention, as if they might very well be happy if I learned in some painful or frightening manner. To your question Jim, no I am not afraid.”

“Mrs Jones must be terribly tired from her journey. In the morning I’ll give you the tour. I think you’ll be pleased.”

“Thank you Mr Curtis. I look forward to it. Goodnight gentlemen.”

Ling had set Alice’s small bag in her room. The interior designer had listened to what had been asked. Alice could tell that she had an intuition, something that cannot be taught. There was a small wood stove in a corner. Bookshelves lined an entire wall. There was a stuffed chair on a rug. Her bed was beautiful, but simple. The designer had considered the problem of laundering fine fabrics out here. Above her bed was an oil painting of the desert.

In the morning Mr Curtis gave her a tour of the immediate property. Nearby was a spring. He had built a stone lined trough into which a spigot flowed freely. There was also a hot spring naturally lined with pebbles. Cottonwoods had been planted in rows. Mr Curtis said they would reach a great height in a few years. The house was basic, but very comfortable. There was a barn and a small, comfortable house for Ling. All the structures had been painted white as she had asked. Mr Curtis said her trunks along with provisions would arrive in a couple of weeks. He thanked her for her business and headed back to Reno. Alice remembered that first night alone, Ling was there of course. She hadn’t slept so well in years. She felt she belonged to this place and it eased her mind because she had given consideration to what Micheal would have wanted for her. He had indulged her love of the West, which seemed a fad among her peers. To them it was a surface fascination. They denigrated the newly monied and the coarseness of boom towns, which to them included even San Francisco. And secretly they wanted a romance with a cowboy. Unlike Alice, they didn’t understand the difference between a vaquero and a cowboy. After Micheal died her friends, as she had once called them, were scarce. Perhaps they found her a threat. She wasn’t considered old and was quite beautiful even if she had been. No matter.

In the morning Ling served eggs, toast, tea, and coffee. Alice had tried to make conversation with him, but he did not speak any English at all. Well, she thought, they would work on it. When her trunks arrived Ling helped her put her books into the shelves and set up her typewriter on the porch. Most of the other supplies went to the pantry and barn. She sat at her typewriter and looked out at the desert just as she was doing now. She knew she was being watched. Just curious, she thought. She saw through their eyes, a white lady alone in black with a Chinese man. Very curious indeed. And now, she sat punching away on a strange machine. A couple of braves had come to the spring earlier and she didn’t bother them. She wanted people to know they were welcome to the water. She was surprised how many visitors she had to the spring, animal and human. Freighters, families traveling to Reno, vaqueros, Piutes. And they were all drawn to her porch. She didn’t blame them. It was the sound that caught their attention and then the lady in black. She gave them a little tour of her machine and told them what she was doing. Most seemed to think it was a perfectly reasonable thing to do. She always had new material for characters.

Over time she and Ling were able to communicate. He outpaced her in learning a new language and so even though she had an interest in learning Chinese they increasingly spoke in English. She learned that he didn’t know if he had any family left. He had worked on the railroads, then in mining. He had gotten a job as a cook in Reno and found the work enjoyable. Alice asked if he was lonely, but he didn’t know what she meant. Whenever they needed supplies Ling went and spent a few days in town. One morning while she was having her breakfast Paiute braves approached the house. She thought they were going to the spring, but they passed the water and started whopping and crying out. She didn’t know what they might want.

“Ling!”

“Misses?”

“Make some corn cakes and a little pork and bring it out here.”

Ling brought out the corn cakes in a huge stack with a plate of shredded pork. The braves came and took a cake and grabbed the pork with their fingers. They ate and left. The following week, they approached in the same manner, whopping loudly. And so it became a weekly tradition that Mrs Jones served corn cakes and shredded pork on Saturdays to whoever happens by. And then he came by one afternoon. Jeffry. He was working the Smoke Creek range nearby and was after stray cattle when he neared her place and went to the spring for water. He came to the porch like everyone did.

“Howdy ma’am. Mind if I water my horse?”

Alice looked up at him and felt struck. Suddenly she felt shy.

“Please, help yourself. You never have to ask to take water.”

“Obliged ma’am. Names Jeffry.” He held his hat in his hands and she could see he had blonde wavy hair. She was tongue tied, so she just smiled at him. She didn’t see him again for quite a while, months. She thought about him often and hoped she would see him again. He stopped by again in the spring. He came to the porch to say hello. She wanted him to stay so she invited him to have lunch with her. He said he’d be grateful. Ling made a chicken dumpling dish.

“Can’t say I’ve eaten anything so delicious.”

“I am spoiled with Ling. I’ve come to adore Chinese food.”

“Next time in Reno I think I’ll find my way to Chinatown.”

“You’re always welcome to stop here for Chinese food.” She flushed. That was a little forward, but it’s what she wanted to say. She raised her eyes to his face and he looked right into her. She thought he looked a little nervous.

“Obliged for the meal ma’am. I ought to be gettin back now.”

He came again a couple of weeks later. Each time they had lunch on the porch and talked. She learned he had been working cattle ranches since he was a boy, that he never married, that he loved his work. And then he came one week when Ling was in town. Alice made them ham sandwiches and tea. She had reached out and taken his hand. She held it, turning it over. So rough, she thought. She led him into the house. He visited every week for a decade. She had finished several novels by that time. She will never forget the day a rider came at a fast trot, a line of dust rising in clouds– looming large behind the small rider. And then he dismounted and walked slowly towards the house. She had seen him before, a vaquero. He took his hat off.

“Mrs Jones, ma’am. I have some bad news about Jeffry.” He looked at her seeing if he should go on. Alice’s mind simultaneously raced and froze.

“Jeffry was killed. Murdered. I’m sorry.”

When Alice could finally speak she asked for the details. Jeffry had just been paid. He was robbed and murdered.

Alice wiped her eyes again with the handkerchief and looked out into the desert. She pulled the page from her typewriter and set in on top of the stack to her right.

The Vaquero

by A. Jones

The Cougar

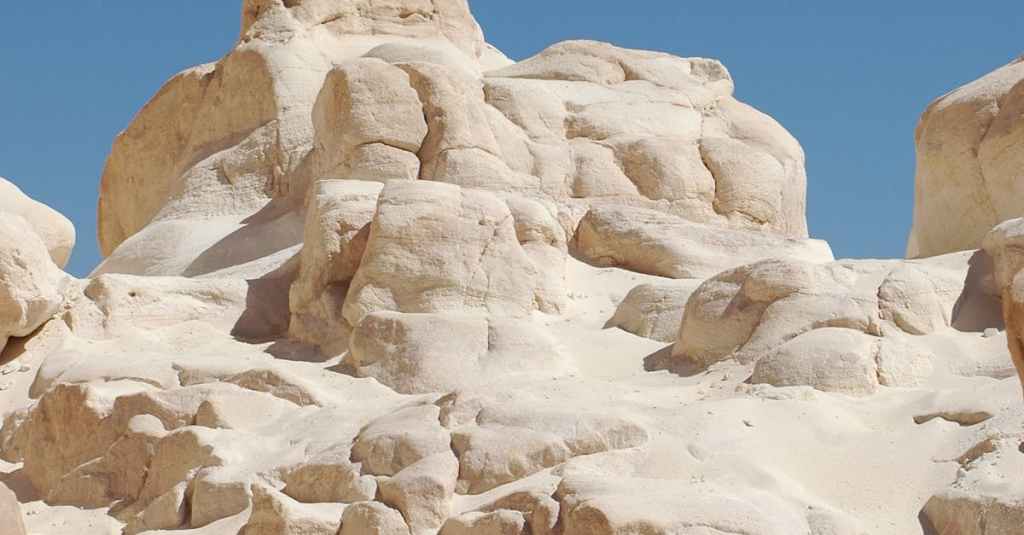

Collin slid into his pack and continued through the canyon. The walls sloped near the bottom spilling water eroded bentonite clay. Layers of sandstone, more resistant to weathering, jutted out in rough edges. Collin was reminded of a Gothic cathedral–the Sagrada, he thought—and like the cathedral still being formed. Before his trip he had visited the Nevada State Historical Society and spent weeks pouring through John T Reid’s donated books on mining, history, and archaeology. The collection was available to mining experts and scientists. He was most interested in King’s 1868-1871 40th Parallel Survey and notes by Reid himself. He had made exploratory trips into the canyon over the past two years convinced it would yield precious fire opal. During each visit he had buried a cache of water in preparation for a prolonged study. And now he worked down the canyon making test holes. According to the land survey the canyon was ten miles long with an average depth of 300 feet. He had parked his fully stocked, off-road accessorized Jeep as close as he could get to the entrance and set off on foot. Opals formed when seeping water deposited silica in cracks and pockets. The gel-like substance solidified over millions of years forming tiny spheres that reflect light in brilliant display. Collin had found some surface opal and some promising excavations that he marked with posts for deeper digging. It was his fifth day in and he had reached the end of the canyon. Miles of playa spilled out in hues of cream and orange. In the morning he would work his way back digging along the opposite wall. Collin stopped to make camp. Starting a fire he heated a package of chicken curry and read from De Re Metallica. First published in 1556, translated into English in 1912 by mining engineer and US President Herbert Hoover, the book was still studied at universities such as Colorado School of Mines. Collin delved into the old for overlooked or forgotten bits of insight and wisdom. He also brought Louis L’Amour’s Comstock Lode–he could read and let his imagination drift. He loved any story, fictional or otherwise, on the topic of the west or mining. Some of his best scientific insights had come from fiction. He was of the opinion that there was value in thinking like an artist, without limitation. The air had been unusually still and the days quiet and warm. Collin had been so focused on scouting he hadn’t noticed. At night the silence amplified, demanding attention. Collin couldn’t explain it scientifically. A plausible explanation might be that the reduction in sight heightened the sense of hearing, he wasn’t sure. The canyon was sparse of vegetation and wildlife, a few rattlesnakes and rodents. He finished his dinner and dessert of dried fruit, made his camp neat and crawled into his tent. He read from The Comstock Lode before falling asleep. Deep in the night he was awakened by the scream of a mountain lion. This was an unusual place for a cougar to roam. There were rabbits, antelope, and springs in nearby mountains. But this canyon was surrounded by playa and generally the cougar did not like flat, open expanses. Collin fell back asleep. In the morning he made coffee and ate a dense bread loaded with nuts and spread with almond butter for good measure. He would need the calories for carrying his supplies and shoveling. His method was to carry only necessary supplies. He returned at the end of the day for the tent and large pack and moved to the next camp spot. As he got his day pack ready with snacks, water, and tools he noticed lion tracks. Collin wasn’t uneasy. The lion was probably just curious. He headed down the canyon observing the tint of the rocks. Sometimes it was just a feeling that led him to a location. He knelt down to dig. Immediately he found precious opals–brown and rough, a light hit of the chisel revealing flash and flame. The allure of opals, he thought, was not just their beauty but that they appeared to contain something—a worldscape, a universe, and in this case fire. He continued to dig further. His shovel came in contact with a large rock with perhaps a diameter of 25 inches. That was not unusual. The soil looked soft, but was full of rock. Collin inspected its brown moonlike surface. Carefully, he glanced it with his chisel. Opal. Probably aggregate, he thought. He got his small pick and brushes and spent the day cleaning it. Brushing away loose dirt broken free with the chisel revealed bone. It wasn’t unheard of to find opal in fossils. Once, while on a dig in Oregon, a colleague unearthed black opal formed in a fossilized snake head. After a couple of hours of careful work he could see what looked like an orbital socket, opal inside. Some of the opal in the rock separated into smaller stones. He didn’t want to get excited about the possibility that a single opal filled the fossil and he couldn’t make out the size of the bone yet. By late afternoon he had exposed enough to know–not know exactly because it was foreign–but have some understanding of what lay before him. It was clearly humanoid. The brain cavity was exceptionally large. It was filled with what appeared to be a single opal. Collin wanted to get some help in uncovering more of it, not risk damaging it. It was too heavy to carry, so he disguised it in place. It was getting late and he decided to camp in the same spot he had the night before. The possibilities of what his find meant occupied his thoughts as he heated his dinner and watched the flames. He knew about Reid’s discoveries in the Lovelock Caves. Some of that research and the actual skeletons were restricted even to him. He also knew of the Paiute stories about a race of giants. In fact, when Reid was a youth he had spent much time talking with Sarah Winnemucca. Collin knew that he had found something special. He planned to continue his test digging in the morning. There was a reason he was drawn to this canyon, perhaps there was more to find. That night he was again awakened by the sounds of a mountain lion. It sounded as if the lion were fighting something. It was well past mating season. Collin was perplexed, but he fell back to sleep with his pick ax in hand.

After coffee and a hearty bread and nut butter breakfast, Collin continued through the canyon with his day pack. As he started to kneel to dig something caught his eye, a graceful movement that his body registered with fear. He turned and looked into green eyes. The cat was black. Collin couldn’t believe what he was seeing, but averted his eyes and stood, slowly raising his hands above his head. He banged his metal tools together and took careful steps backward. He looked at the panther’s body. It hadn’t moved. And then suddenly it turned and ran. Collin was awed by its beauty. Was that the cougar he had been hearing? He had read about sightings in New Orleans and even in Marin County in the 1940’s, but never this far north. He made his way back to camp. He’d head out tonight and come back another time. As he hiked out he tried to make sense of the experience. He wasn’t dehydrated or low on electrolytes. He had seen the prints, so it wasn’t a figment of his imagination. What was Reid’s theory on the ancient race of giants? He had believed they were the ancestors of the Mayans. A complex stone calendar was one of the findings in Reid’s collection and he had studied the petroglyphs and found commonalities with the Mayans. Collin gathered his supplies together and started back. He had several precious opals with him. He thought about the skull. The black panther in Mayan culture symbolized a connection between the dead and living and was seen as a protector. What was the message? Should he leave the skull buried or should it be shared? Who would it benefit? If it belonged to the same people Reid had found would it be written about? Those bones had been shelved in the dusty backrooms of museums. If people knew anything at all of their culture, it was myth. Collin was tempted by the find, the skull and fire opal that might possibly be the largest ever discovered. He searched his soul as he continued. It was dark when he reached his vehicle. He loaded up his supplies and was enveloped by the night. He sat on the hood of his Jeep and listened, really listened. The matrix of being pulsed in his ears. He saw the shadow outline of the panther, the green eyes looked into his. He got into his Jeep and drove. He knew what he would do.

The Sheepherder

Bolivar climbed the mountain following his herd. Their bleating and wooly scent the backdrop of his world nine months of the year. It was July 1st and grazing had just opened in the Warner Mountains. They started up at the south end of the mountain range– where the inclines began sandy and steep. They’d reach the first pasture by afternoon. He’d set up camp and then do some training–four laps around the sheep. Each lap might be several miles. The pasture was thousands of feet higher than the valley and spring would still be lingering there. Early in the season he had stopped at the Sawtelle Hotel in Eagleville. Emma, who ran the place, was always kind. She made a Basque dish she called “beef stew.” She served it to Bolivar with a wink, “Marmita,” she’d say setting his bowl down and they’d laugh. She’d always ask if he’d like a little Picon. He declined this time. He told her he was training for a race, a marathon. It was 1907 and long distance running events were becoming popular. Usually they were advertised a couple of weeks before the event, but this one was advertised months in advance, perhaps a new marketing tactic. He pulled out the San Francisco Chronicle folded in his waist band and opened to the page showing Emma.

“Look. November 1st. 28 miles. All the crack runners in California will be there.”

Loud laughter interrupted him. Emma turned and gave them an eye.

“You boys shut it! Hear.” No one liked to get on Emma’s bad side.

“Come on. It’s jus hilarious thas all. This sheeps boy here running a marathon.” The two ranch hands started laughing again, hitting the table with their fists.

“Out! You stay out until you can behave. Hear!” Emma kicked them out.

Emma told Bolivar she was excited to see how he’d do in the event. She knew he’d finish. Bolivar started running in the valley. It was often hot and it was flat. If he saw a cattleman or ranch hand he’d stop not wanting to start any problems. The two at Emma’s had told their co-workers about him entering the marathon and the entire valley knew about it now. They were calling him “marathon boy.” He didn’t mind the name. If it was an insult they should have come up with something better.

They had reached the high pasture. The sheep spread out and grazed. Bolivar set up his canvas tent, put all his gear in there and set out at a jog. He liked to warm up and get faster with each lap. The pasture was on a slope and he moved into the trees at times. It was grassy, rocky, there were downed logs and a few snow fields. Perfect for training he thought. The race course was advertised as hilly, but on maintained coastal roads. He completed the laps in three hours. Bolivar made a fire and heated his dinner, mutton stew and bread made in a cast iron pan. After cleaning up, he went into his tent with his lantern and got a book out of his bag, The Virginian. He chuckled thinking about the reaction people might have if they knew it was his favorite book. They were all herdsmen. They all wanted the same thing. His page was marked with a clipping from the San Francisco Call, August 5, 1896. Spiros Louces Visits Berkeley. Spiros had won the gold medal at the revival of the Olympic Games in Athens. He was a shepherd who trained in the mountains carrying water from camp to camp. Bolivar was inspired by his story. He had never thought about running as a competitive sport before reading about Spiros. He read from his book, “Daring, laughter, endurance–these are what I saw on the countenances of the cow-boys.” He re-read the same line three times, his eyelids too heavy to keep open. Bolivar blew out his light and fell asleep.

He was awakened by laughing and the sound of boots, loud and sporadic like stumbling.

“Marathon Boy!” They laughed. They were drunk. They must of ridden up here.

“Let’s pull em out.” One of them said. Bolivar decided to get out and face them. He didn’t want to have to shoot these idiots, but he didn’t think he could reason with drunk men. He got out of his tent. There were three of them including the two from Emma’s.

“What do you want?” They were laughing and not steady on their feet. Bolivar was sure he could outrun them if needed.

“Les cut his tendon.” The tall one said and snatched his leg is one swift movement. Bolivar was knocked onto the ground.

“No, let’s smash his foot with a rock. Id look like an accident.” More laughter. Bolivar would wait for the right moment to run.

“Hey, I thought we was jus gonna scare him! I don’t want no trouble. Jus thought we was gonna ‘ave a little fun.” The tall one punched his companion. He fell back unconscious.

“What’d the hell you do that for!”

“Cus I damn well felt like it!” The tall one swung for him, but the other ducked and punched him in the stomach. Bolivar was free now and the scene was feeling comedic. The tall one and his buddy were in a full on fight. The shorter man prevailed and stumbled away mumbling something incomprehensible and shouting.

“Jus… lil…un. Da…ards. Larry!”

Bolivar didn’t want to be in the area when the two men woke up. He remembered that line from The Virginian he liked: It’s not a brave man that’s dangerous…It’s the cowards that scare me.

He broke down his camp. His leg was wrenched pretty good, his knee throbbing. He hobbled with his gear up the meadow towards the trees. Bolivar didn’t get mad easily, but he felt heated thinking about those dunderheads messing with his training. Calm down he told himself. He’d rest up a few days and take stock then. See what’s what. He always kept medical supplies with him. He drank willow bark tea and applied arnica root to his knee. He felt better after a day, but he’d be patient. After three days he was ready to run again. As the weeks progressed, he moved his sheep to higher pastures keeping his routine of lapping around the sheep. He wasn’t bothered by any drunk ranch hands again. In the fall when the mule ears dried out and the Aspens showed yellow they moved lower until finally they were back in Eagleville. The end of grazing season in the mountains was October 31st, but Bolivar came down a week early to travel to the race. Emma met him at the stage, hugged him, and wished him luck. He’d take the stage to Reno and then the train to San Francisco.

Disembarking onto the platform in San Francisco, a group of young ladies held signs welcoming the runners. Bolivar blended into the crowd and made his way to the Argo Hotel on Mission. The clerk at the hotel asked if he was running the marathon. He was going to say no, but changed his mind. The clerk smiled and welcomed Bolivar to San Francisco. The porter led him to his room on the second story facing the city. He lay on the bed and closed his eyes walking through the course description in his mind. It would start on the waterfront, go through the Golden Gate Park, along the ocean, then turn up into the country, and return. He didn’t know what any of the area might look like. Bolivar made his way to the lobby. The clerk recommended a restaurant nearby. People on the streets were talking about the race. He heard bets being taken. That made him feel nervous for some reason. After dinner he made his way back to his hotel. The race started at 10 AM the next morning.

Bolivar woke at 7 AM and put on linen pants and soft leather shoes. He wasn’t used to the humidity and it felt cold even though the temperature was warmer than the mountains he came from. He put on the thick wool sweater over his long button up shirt and made his way down to the lobby. Breakfast was being served buffet style. He was surprised to learn some guests had come down to see him off. Bolivar had read about athletes hydrating with alcohol. He wasn’t sure if it was really meant to hydrate, maybe ease discomfort. Spiros had sipped cognac on the way to his win. In his training, Bolivar found drinking from the springs worked best for him. He had tried whiskey, water was better. He walked towards the starting line, the crowds already deep. He weaved his way through to the start. A couple dozen men stood near the start, lean and sinewy. A few wore rubber soled running shoes and cotton shorts. The announcer climbed a ladder and spoke into the mega phone. Bolivar paid close attention to the course information—marked with flagging, one water stop. Without warning a pistol sounded and the runners took off at a break neck pace. Spectators ran into the street yelling, the runners darted back and forth to avoid collisions. Horseback riders trotted alongside throwing candies. It was too soon for food, but Boliver grabbed a few for later. Golden Gate park was beautiful–manicured like a garden. Automobiles joined the course. The race made its way downhill to the ocean. Two runners ran down onto the beach and got into the waves. Bolivar pulled his sweater off and threw it on the road. He heard screams and turned to see a group of girls swinging his sweater over their heads. He waved at them. The lead runner was ahead in the distance. A car pulled up beside him and handed him a drink. Bolivar counted ten runners ahead. The course turned inland, climbing into tall trees. The road was muddy, a little slippery. He wondered if rubber soles would have better traction than leather. He passed a couple of runners on the climb. The spectators thinned to those with a buggy, or automobile, or on horseback. He was looking forward to a drink of water. When he got to the table there was only alcohol. With a smile, the volunteer said that he’d dumped all the water, donating the liquor to the runners out of his own pocket. Bolivar thanked him and ran on. He was sure he’d come upon a spring in this forest. Something hit him from behind. He rolled several times before coming to a stop. The runner laughed and ran on. He wasn’t going to get angry. Waste of energy. Patience. The hills were his strength. He’d get him on the next incline. He ate a candy and saw a spring ahead. Getting back onto the course he started making ground. He increased his pace gaining on the runner who pushed him. Bolivar leveled up with him on the hill. The runner’s breathing was labored, Bolivar surged ahead. He heard the man swear. They made the turn around. Fourteen miles. Time to work. He realized he had only seen five runners heading back. The others must have dropped. He felt a little adrenaline. Stay controlled, he told himself. He drank again from the spring and ate another candy. Turning onto the ocean front road, he could see the leaders about half a mile ahead. A car pulled up along. The passengers passed them food, drink. Bolivar didn’t know what it might be. The onlookers were getting excited as the leaders closed the gap with each other. The girls were still there with his sweater. They waved it, cheering for him. Turning up the hill towards Golden Gate Park, he made ground on the lead pack. They were less than a quarter of a mile ahead now. One in shorts doubled over and sat down. Could he pick off one more runner, finish third? He worked the hills, his breath coming loudly now. He closed the gap with the runner in third and sat on his shoulder before making his move. The crowds were frenzied, squeezing onto the street making the route narrow. Bolivar pushed, and passed second place. The runner in first place looked back. Bolivar saw his expression and surged into a sprint. The finish line in sight, Bolivar moved ahead of the leader. He raised his hands up crossing the tape. He was smothered by the cheering crowd. After giving interviews to the press he went back to the hotel eager to change his clothes and eat. Guests were waiting for him offering him food and drink. The front desk manager said that there was no charge for his stay, they were honored to have the winner of the marathon at their hotel. Bolivar decided to stay one more night and explore the city. On the train home he replayed the race in his mind. It had been a perfect day for him. San Francisco aroused his senses, but he missed the high desert. When the stage approached Eagleville, he saw a large group of people waiting. Music drifted across the flats and then closer, the smell of barbeque. People had come from all over the valley to congratulate him, including ranchers and buckaroos. He felt lucky to live in this place still holding on to old ways. If differences were set aside, they could all flourish. He looked at his neighbors and recalled a warning he had read in the Silver State:

“…the ranges for both sheep and cattle will inevitably grow less…and the cowboy and the sheepherder will inevitably be things of the past. When they finally disappear an interesting and exciting epoch of frontier life will have passed.”

Spyridon Louis, 1896 Olympic Gold Medalist Marathon

The Spinster

Jane’s black taffeta dress rustled like Aspen leaves in the fall. She was aware of eyes on her. “…Mourning and crying and pain will be no more, for the first things have passed away,” the deep timbre of the pastor’s voice washed over her. She looked up at the snowcapped mountains behind the cemetery, the preacher’s voice receding again. A warm breeze carrying the smell of spring sage reminded her of the day she first set eyes on Samuel Monroe. She was in her study, grading eighth grade final examinations, and had gone to the window to watch the lamplighter’s as she sometimes did. He rode by on a palomino mustang. She felt an energy, presence around him even from that distance. She didn’t believe she was infatuated. She told herself not to think about him. Her brothers would never approve. Besides, he had no idea she existed. Jane was aware of people moving towards their horses and conveyances. She placed a bouquet of Lupine on Sam’s casket and walked to her carriage. She looked at the vaqueros mounting their horses, they nodded to her and headed towards the saloon. She remembered where they had first met. She walked down Virginia Street to John Cumberland’s to pick up the shoes she had ordered and there he was. Her heart raced and throat tightened but she managed to smile at him. He was polite, simply said “Ma’am.” How she saved that, re-played it again and again. She pretended to shop so that she could watch him. She heard him say he just came off the Jackson Creek range as he set his boots on the counter for repair. She liked his hands. After he left she quickly picked up her order and followed him down the street, stopping to look at the shop fronts. He entered the saloon and she continued home. How would she meet him again? Perhaps she could send a calling card. That would be too forward, they hadn’t really met, not properly. She looked through the stage window admiring spring in the high desert. Her east coast friends did not understand this country. To them it was desolate, formidable in its stark contrasts. She smiled seeing a herd of antelope run not far off along the stage. Forsaken, she thought, to those without eyes to see. That summer she first saw Samuel, she made a habit of watching the lamplighters each night. She learned he came into town the second and last Friday of every month. The Liberty Hotel was hosting a dance every night of the Fair–residents and out of town guests welcome. Jane had spent the warm nights attending high society dinners and balls, usually held at an estate or mansion. She wandered through these a ghost, her thoughts circling Samuel. The smallest details kept alive by turning them in her mind. Determined to attend the public dance, her brother Alexander agreed to escort her. The carriage jostled through a wide washout left by melting snow. She was thirty nine, very young looking. She gave her age as twenty nine. It didn’t matter now that she had lost Samuel. She would teach. She supposed they would expect her to attend dinners and social functions soon. She would go through the motions, do what was required. A local orchestra and vocal quartet played the night she was introduced. The ballroom was decorated with flowers and streamers, punch and refreshments were served. Jane had asked her brother to introduce her. Alexander hadn’t asked any questions–how she knew his name even–he immediately liked the looks of Samuel.

“I am Alexander Morgan and this is my sister Jane.” Alex reached his hand out.

“Pleased to meet you, Sam Monroe.” Alex and Jane both smiled. Jane was waiting, hoping. Sam was a gentleman.

“Ma’am can I ask for this dance?” Jane blushed and giggled and held her hand out for him to take.

The wind had picked up knocking the carriage from side to side. Dust devils formed in the distance, touching down and spilling their dirt in big clouds, then gathering up again into funnels. Samuel had asked for one more dance later in the evening and then Alex suggested he and Jane head home. Jane went through the evening in her head, savoring the moments close to Samuel, touching his hand. He had asked other ladies to dance. That was perfectly reasonable. More than two or three dances with one person gave people ideas. Now that they had met she could send him a calling card. Close to its rough past, Nevada was casual. Her rank liked to imagine themselves at the greatest heights of sophistication and propriety. Jane found it stifling. She had sent the calling card and waited for a response. It was possible he didn’t receive it. It was also possible he didn’t know the etiquette in responding. Jane began pacing her room at night unable to sleep. Her thoughts narrowed on a few details and encounters– closing, focusing until there was little else. Her carriage turned onto Virginia Street now. That winter she had become a shadow of herself. Her family worried she was consumptive. She had lost weight and didn’t seem to take joy in her teaching. It was the second Friday of the month in May. She remembers it clearly. She went to the street and waited for him to pass. He went to the saloon as usual. She doesn’t remember what time he left, but she can see him walking out, so handsome. She shocked herself walking up to him. “Hi Samuel.” He smiled, but there was no register. He didn’t remember her. Jane shocked herself again. She kissed him. He was a gentleman. He didn’t tear her away forcefully. He held her, arms straight out and said, “Excuse me ma’am.” Jane was embarrassed, angry. She took the Bowie knife she had brought with her and stabbed him in the heart. He slumped in the street and she ran. She heard shouts after she turned a corner. She ran to her house and up to her study. In the morning, the front page headline of the Gazette read: Beloved Vaquero Stabbed to Death. The article stated they had no idea who killed him or why. He was liked by everyone. It was a mystery they would be investigating. The carriage stopped in front of her house. She got out and looked at the dark, quiet house and made her way up to her study.

The Mustang

Helen sat crossed legged in the shade of a mesquite bush waiting out the heat of the day. She didn’t know if they were still trailing her. Inspecting the hem of her red velvet dress covered in grey dust, she scooped dirt and covered the entire gown. Her hat was lost a few days ago at the edge of a spring she had bent over to drink and smear mud on her face and chest. Her only possession, a satchel containing the cash she was planning to use to buy out and a jar of tallow moisturizer. She appreciated the tallow. Fear prevented sleep. She closed her eyes and listened. She liked having this desert to herself. Miles, distance were safety. She would be patient, smart–move at night and rest in the day. Without water this was the only way to survive. People tended to be afraid of the desert at night. Not Helen. She knew the creatures there didn’t want to be bothered same as her. She waited for the sunset to move. The desert came alive with sounds, insects, owls, coyotes. She felt energized by the night air and safe, hidden. She had the advantage on foot. A rider couldn’t sneak up on her and she could hide in the dark. She had learned a way of becoming invisible by covering herself in the loose sandy earth. A regular told her about it. He liked to talk about warfare, especially tactics he learned from Indian warriors. She tucked some of those ideas away in case it was true you couldn’t buy out–moving at night, using mud as sunscreen were some of the things she remembered. The sound of hooves beating sand crescendoed. Heart racing Helen hid behind a bush. Her breathing was too loud. They could hear her, she thought. A velvet nose nudged her from behind. Helen screamed. She realized the horse had no rider or gear. She looked over at the other horses. Wild mustangs. She put her hand on his cheek, shocked he let her touch him. After her heart stopped pounding she continued on. She needed more distance. The herd moved with her a ways off. She thought about something she read in the paper about claiming a homestead. What had it said?

He or she must be a citizen of the United States.

The settlement begins by erecting or purchasing a dwelling house.

The claim is maintained by improving the land.

She’d have to go into the Land Office, give her name. A widow was respectable, treated kindly. What name would she use? She was a Helen, couldn’t let go of that. Helen was the last outward identity of her own she had left. Her heart, her soul…they hadn’t taken, they hadn’t broken her. Baker had a nice ring to it she thought, the kind of name people felt an affection for. Who didn’t like a Baker? A name from a family history of people who baked bread. Helen hadn’t eaten in almost a week. She didn’t ask herself how much farther. She knew those thoughts only invited weakness, little cracks in the armour that could end her right here in the desert. No, she was going to be one of the ones who made it. Helen Baker it was, she didn’t need to think about it again. The shadow of a mountain range loomed in the distance. Helen looked for a place to hide for the day as the sun rose. She could hear the rush of water. She was thirsty, but she would wait. Watering holes, the banks of streams and rivers, those were places you were exposed, vulnerable. She had learned that too. This stream or river was loud, another disadvantage. She might not hear if someone was coming. She’d wait. In the dark, she’d have the upper hand. In the distance she saw two men on horseback. She took a broken branch from the bush she was against and placed it in front of her. She didn’t think she could be seen. The men neared. They looked like vaqueros.

“The river is still high. I don’t think any cattle crossed.”

“Boss asked us ta check. We can double back round the mountain.”

She didn’t know how close to a settlement she might be. She planned to go straight into the Land Office in Winnemucca, find a spot on the map, and stake her claim. She’d have to find a way to clean up. When it got dark she went to the river and drank. It was wide and rushing pretty good. She wondered what he meant about doubling back around the mountain. Was there a way around the river? It must start way up in that mountain. A velvet nose touched her shoulder. Helen jumped, but she didn’t scream this time. She saw the herd too. Flowing water had drowned out their approach. The herd went into the river. The horse who nudged her, she couldn’t see what color he was, stayed beside her. What were the limits of her bravery? Her spirit felt larger than the night sky. Nothing could stop her. Helen grabbed his mane and swung her body up and onto his back. She expected to have been thrown off, but the horse walked into the water, Helen hanging on. After they crossed, she stayed on his back. They moved through the night making more ground than she would have on foot. The lights of a town flicked in the distance. That should be Winnemucca. Helen dismounted and thought. She didn’t want to be seen on the streets like this. She walked into the town, careful not to be seen, looking at the shops. One caught her eye–Millinery and Dress Making Shop, Viola Harney. It looked like the proprietor lived on the premises. She squatted in a bush thinking. She would have to trust someone. She didn’t feel so brave now. Patience and smarts wouldn’t help, she needed a little luck. She closed her eyes and waited for the light. At first light she knocked on the dress maker’s door. There was no one in the street. A woman answered.

“I’m very sorry I’m not open yet.” Her eyes widened comprehending what she was seeing. “Come in.” They stood looking at each other Viola in shock and Helen frozen with fear. “I’m Viola.” Her large dark eyes were kind.

Helen found her voice. “I need a dress.”

Viola got her tape measure and did some quick calculations. “I have a couple of dresses my clients didn’t pick up.” She went to the back and brought out a cotton dress, cream with brown and blue flowers. “This may fit, I’ll have to take it in a bit.”

“No,” Helen said too quickly. She looked away embarrassed.

“How about this,” Viola said, “I have a basin in the kitchen. I’ll start boiling some water and you can get cleaned up. Then you can try on the dress.” Helen started shaking. She couldn’t remember such kindness. She couldn’t get words out.

“Take a seat here.” It was a wicker chair. She left to get the water boiling. Helen could hear noises in the kitchen. She smelled eggs, bacon, coffee and was overwhelmed with hunger. “While the water’s heating, let’s have a little breakfast shall we.” Viola handed Helen a plate with four eggs, four thick slices bacon, and a hunk of sourdough. She set butter, jam, cream, and coffee on the little folding tray painted black with bright florals. Helen tried to eat like a lady. She was eating too fast she knew. When she finished Viola asked if she’d like more.

Helen’s voice was stronger, “Yes, please.” Voila brought out a plate of the same and poured more coffee for the both of them. After her coffee she went back in the kitchen to finish the bath.

“The water’s warm. There’s soap and a towel. I set the dress back there since you probably don’t want to get into a dirty one after a bath.”

“Thank you.” Helen thought she would cry. The bath felt wonderful. She wanted to linger, but was eager to get to the Land Office first thing and stake her claim. The dress fit a little loose, but looked nice–respectable. She came out into the sitting room and Viola smiled. “You look beautiful.”

“I can’t thank you enough. You can’t know how much this means. Please, how much do I owe?”

Viola took Helen’s hands. “You don’t owe me anything.”

“Please, I’d like to pay you. For the breakfast too.”

“Whatever it was happened to you, leave it behind. You step out this door and you never look back hear?” Helen nodded. She lost her voice again, turned and made her way to the Land Office. The man at the Land Office showed Helen the map where she could find an available homestead.

“These ones here all along the creek here are taken, see. Now there’s some promising property up here. There’s water, some mountain, flatland too.” He lifted his visor and looked close with a magnifying glass. “Thees the coordinates. We’ll have to put that down. Widowed did you say?”

“Yes sir,” Helen nodded looking at the map.

“Desolate country up there .You got some help?”

“It’s just what I’m looking for. Can we take care of the paperwork now?”

“Yes ma’am we surely can.” He got the forms and filled in all the information required. “It’s recorded right here.” He showed her the log. “You’ll need to prove on it, got a year, or pay up. Course there’s taxes too can’t forget that.” Helen nodded.

She thanked him and left for the lumber yard. She ordered enough lumber to build a house and asked about a contractor. The lumber man said Andrew, who would deliver the lumber, might be interested. Helen purchased a wagon and team and stopped at the mercantile to stock up on supplies including pants, a man’s shirt, belt, gloves, a rifle and ammunition. She left town headed for her property. The trip took two days. She fell in love with it when she saw it. Half the land was mountain, the other half flat, sagebrush and juniper dotted. She spent the day exploring it, cattle country she thought. She had enough to buy breeding stock. She found a hot spring near the base of the mountain. This is where she’d have her house built. She’d use the wagon as shelter until then.

The man from the lumber yard came out a few days later. She showed him where she’d like the house built.

“Good spot to build. I’d ‘ave picked it myself”

“Please call me Helen.”

“Okay then. I’m Andrew. I’ll hire a few hands in town. We could have your home finished before the fall.”

Helen smiled. That summer she spent her days wandering the mountains while the men built her house. She liked the solitude, she felt safe. In the evenings she sat in the covered wagon and made plans for her ranch. Andrew and the workers camped under the trees not far away. In the fall when the finishing details were being completed, Andrew did a walk through with Helen. Stepping onto a wide covered porch the front door opened into a spacious living room with a stone fireplace. Off the living room there was a kitchen with cupboards, wash basin, and fire wood stove. Two bedrooms were accessed off the main room. Advertised as leak and fire proof, the roof was metal. Helen smiled as she walked through the spaces. She could imagine a good life here.

“I’ll return with your furniture order in a few weeks. I’ll let you get settled in.”

In the morning Andrew and the workers thanked Helen and headed for Winnemucca. Andrew would return with the furniture and then make another trip with more lumber for the barn. Helen wanted to fence in three acres around the house and barn, but that would need to wait until spring. Helen set up a cot in the living room, started a fire, and imagined her ranch. She’d start with 10 head. She’d need a couple of hired hands. The cattle could roam the mountains in the summer and move down to the flatland in the winter. She’d keep the barn stocked with No 1 Hay. She had enough money to finish the barn and buy the cattle. She’d start small and build. She’d be smart, learn the ropes first. The sound of hooves beating the ground shook her out of her thoughts. She ran out to the porch and saw a herd of mustangs in the flatland. She didn’t know if it was the same herd she encountered in the desert.

Andrew rode up two weeks later with her furniture. She helped him unload it and carry it into the house–a bed, dresser, couch, side tables, lamps, rug, and blankets.

“There was a stranger in town asking around about a Helen. Couldn’t give a last name. Didn’t like the looks of him, said I couldn’t help. Do you know him?”

Helen shook her head. She was trembling. “What’d he look like?”

“Big black beard, bluest eyes I ever seen, thickly built.” Helen felt sick.

She had come so far. She didn’t think it would occur to him to go to the Land Office. Maybe he would ask everyone, visit every business. If he didn’t give a last name maybe people would be suspicious like Andrew was. Whatever Helen’s last name was, she didn’t know it either. All of them had a first name only. She picked Helen. That was her name. Maybe it was foolish to have kept it after all. She wanted to ask Andrew to stay, but that was not possible. Andrew said he’d return in another two weeks with lumber. He’d bring the crew again and the barn would be finished before winter. After he left Helen loaded the rifle she bought, went outside and made a few practice shots. Nothing to it she thought, except when your nerves have you shaking. Could she stay in control? She trembled hearing his description. She’d do like she done in the desert, stay awake at night, sleep in the day. She would move up into the mountains on foot, find a good place to sleep. At night she’d watch out the window, lights off, with her rifle. It was nearing the day Andrew and the hired hands would return. Helen was feeling better, less on edge. In the dark she heard the snap of a branch. An animal probably. She was alert, watching. She was overcome with nausea when she saw the figure of a man. He was approaching the house, moving behind trees as he went. When he moved again she fired. He ducked behind a tree. He was laughing, insane, crazed, striking fear into her. He moved and again she fired. He was on the porch now. Should she stand her ground or slip out back. She tried to remember the tactics of the warriors. Which was better? She felt claustrophobic. She moved lightly, quietly out the kitchen door. She heard the awful laugh again and loaded her rifle. He reached out and grabbed it forcing it upward and punched her like a man.

“Bitch! No one steals from me!” He spat on her. Helen was knocked out.

A whinny broke above his insane laughter. He turned, hooves in his face, landing on his skull. He couldn’t see now, stomping. Hours later, Helen opened her eyes. There was a Mustang standing near. She took in his colors, buckskin with dark stockings–stripped at the knee.

Reno

Reno blinked at the ceiling. What sort of end was this for a man who lived outside half his life. He hadn’t thought of his father in decades, but it hit him that he died much the same way— lying in bed waiting for the end. Lucky bastard. Had only to wait a year. In that time plotting the murder of his wife and shooting squirrels. Crazy bastard. The San Francisco Chronicle reported he killed 750 squirrels the day before his death–all from his sanatorium bed no less. What year was that? He had just started walking, must have been about 1890. Why had he hung on for all these years? Toughness? Cowardice? Fear for his soul? He knew plenty of vaqueros who had shot themselves. Did he know them or had he read about them? He knew a couple. Suicides in the papers seemed common. Usually in some sad shack out in the desert. Maybe they weren’t so common. Happened though. Lucky bastards. How’d he get here? The years after the accident blurred together, yesterday or a thousand years. Didn’t matter, they were all the same. That man before was someone else. Another man, another life. He peered into his life, a voyeur. Strange. How could he know so much about that man and not know him. He laughed. Did he think he had become some kind of philosopher? If a man spends decades on his back with nothing to do but think, what does that make him. Hell, maybe he was a philosopher. Maybe he should have wrote some of these thoughts down. Too late now. Reno looked out the window. Cars cruised by on the blacktop. Funny. He remembers the same street– dirt, dusty–with horseback riders, wagons. Lying here had made him a time traveler. Changing times are experienced through the motion of life. Like a movie show he saw it, out his window, the papers. An observer, not a participant. Changing times, progress they called it. Funny idea. His life frozen in time for decades, every day the same. Before the accident he remembered he had been a cog in the changing times. It was in the papers. He had driven a car to Nevada from Red Bluff. The roads were rough, had to change a couple of tires along the way. Passable. The papers celebrated the accomplishment. Others followed. Hell. Reno did it, we can too! Strange. The excitement he felt riding that “modern machine.” He didn’t have many regrets. Unusual for a man in his condition. There was nothing he could have done about the accident. That was bad luck. He regrets that celebrated day he drove up the mountains, had forsaken his horse. He didn’t think he had a part in changing much, but he wished he hadn’t gone along with it. He read in the papers the “last buckaroo” died. Here he was still alive. Well, that’s how many of the true ones went out. Nobody knowing. No obituary or grave marker. He’d have a nice grave. That was all arranged. They put his nickname on there–Bingo.

Wilson

Wilson saw Reno ahead moving through the pastel sage and juniper dotted landscape as the last of the day’s sun pierced grey blue clouds. The high desert gave the impression of monotony and barrenness until you got close to it—then its beauty and mystery surprised a person. It was spring when rains fell and things that seemed dead breathed life—flowers bloomed, birds flocked, antelope and deer moved in and bunch grasses grew tall. The cattle had been brought up to get fat on the wild grasses. The vaqueros were beginning the work of herding, branding, and castrating. Wilson loved every bit of this high desert country—the hardness with the bounty. He belonged to it like any of the other plants or animals that lived here. The wind shaped him as it shaped the trees and the alkali dust filled the crevices of his features the same as it settled in the folds of leaf or bark. Sometimes he wondered if his body and spirit were shaped by the life or if he had been molded for it from birth. He wasn’t sure, but he believed it was a life not left without great cost. He had heard about and had known vaqueros, who when drink or years left them as ranch hands, used a bullet or poison to end their loss. Wilson didn’t dwell on it too much, but he hoped to be one of the lucky ones who kicked off naturally at an old age.

Kiyiya

Kiyiya means kind hearted. Kiyiya is given another name, Kate, meaning pure. In her mind she is always Kiyiya. She remembers seeing the first white eye. Wading into the grasses growing on the banks of Cui-ui-Pah she bends over—a fan in one hand sweeps over the grasses and the pods let loose their seeds, collecting in her basket. Not far away she sees the men fishing for cui-ui. She hears the wind and many birds. She feels the sun and is in harmony. The white eye came on horseback–foreign, pale. She does not understand his language. In the village everyone talks about the strange man with hair on his face. Later one comes who is understood. He speaks with the Chief. One Who Speaks comes over many moons. He brings sweet things for the children. She hears that her people are being killed. She is afraid. One day her father brings a white eye before her and says that she must marry him. She wants to run away. His name is Ra-lin. His eyes like the sky. That is the last time she sees her village. She believes she has died–entered another world. She is placed in a strange world with strange people. She is taught to cook in a way different from what she knows. There are strange medicines she does not trust. She is to speak a new language in this other world. Ra-lin is kind, but this is not her world. Her children are born into this other world. In secret she teaches them her language, her ways. She loves her children. She sees that they are part of the new world—born into both. She sees that they are like One With No Home. Char-lie is killed in this strange world. She runs. Runs away. Her heart is shattered. She seeks her people.

The Cave

It was over 100 degrees and he had snow blindness. His hat offered no protection from the gypsum and selenite rich earth, white and crystalline, reflecting the sun’s rays. Boulders lined the smooth edge of a sink Wilson rode along, searching for the entrance his mother had described. Kiyiya said the cave couldn’t be seen from the ground, that there would be a rock that stood out from the others–an oddity among the white, brick red. The cave was concealed above, where the rock met the escarpment. A screech echoed off the cliff walls–two red tailed hawks circled in the updrafts. Wilson dismounted and doubled over with dizziness–blackness and stars whirred around him. Leandro, nudged him. Wilson grabbed his saddle horn to balance and stroked Leandro’s neck. Unsure of his strength, he started up the chalky boulders. A gust knocked him off balance taking his hat. He watched it tumble and land near his horse. Wilson dropped onto a flat area and peered through the stacked boulders–nothing but playa and a few dusty sage bushes. The cave opened into a cathedral about twenty feet high and thirty feet across. Lighting a lantern he saw that the floor was littered in bones–enormous, human. The hair had been preserved by the cool, dry air–long, curly, and red. He touched it and it crumbled into powder. Remembering why he was here he pushed fear aside. Something reflective was scattered in the light soil. He picked one up–pearls. Glistening like snow, a large, rectangular slab of cleaved selenite stood at the back of the room. The overall effect reminded him of a Christmas snowglobe he had seen in a shop once, but the feeling not so cozy. The air felt ancient. Wilson imagined he was breathing in the giant’s final exhalations. He pushed fear back again before it spilled into his veins. Somewhat out of place reed mats lined the perimeter. Behind the selenite block was another opening–a long tube shaped tunnel. Shining the light into it, he could only see darkness ahead. He bent his 6’2” frame slightly to walk through. It opened into another cathedral smaller than the first. Wilson lifted the lantern revealing human bones, these ones average size, packed deep and to the ceiling. Feeling sick, he ran through the tunnel, through the large room hurdling over bison sized tibias and watermelon skulls and rolled out the entrance, grateful to be in the open on the ledge. In the distance he could see a man coming on horseback.

Helen

After Sam left Jane he wandered the desert unsure of his next move. He rode and camped for days. Hunger drew him toward the homestead in the distance- a neat ranch house under large cottonwoods.

Sam knocked on the painted door. A woman in pants answered. “Ma’am, do you have work?”

Helen looked him up and down. “It’s Helen. You look like a sight. What the hell happened to ya? Been wandering the desert by the looks of it. How’d you get those bruises? Come in. Let’s fix ya some coffee.”

“Much obliged ma’ma.”

“Helen! I can always use help around the ranch.” She set the coffee in front of him along with fresh cream.

Helen sent him to the barn to clean out the stalls and bring in feed and said there’d be dinner ready before sunset. Hattie was at the stove when Sam was called in. She set plates of steak, potatoes, peas, and biscuits in front of Helen and Sam and took a seat.

“Delicious ma’am.”

“Hattie. Glad you like it.”

Helen and Hattie talked business about the ranch while Sam listened.

“Bill n Jack will be finished up with the castratin and brandin tomara.” Helen said.

“I’ll set them on fixin the barn roof.”

“Sam here can do that, can’t ya?”

“Yes, ma…Helen.”

“I need Bill n Jack to pick up some supplies in town.”

“Peas been comin in good. I’ll start on cannin tomorrow. If the boys could pick up some wax.”

At sunrise Sam started on a list of chores–tending animals, gardening, and fixing the barn roof. Each night he listened to Helen and Hattie discuss what needed to be done next, the buying and selling of supplies, cattle, butter and produce in town. Soon he was joining in on their nightly discussions–consulting the Farmers Almanac planning seasonally and according to markets. All aspects of ranching and living on her own were maintained to serve her love of horses and riding. Helen loved being a vaquero. She taught Sam to rope, shoe a horse, make a reatta, handle the cattle, and everything related to being a buckaroo. The first night he heard it he fell out of bed and rolled for his shotgun. A scream like something wild, not human or animal. He ran to the door onto the porch ready to shoot at anything moving when a hand touched his shoulder. He jumped.

“Don’t” Hattie said.

Sam’s eyes adjusted and he saw a woman mount a horse and ride off into the desert screaming something only she knew.

“She comes back without any memory of what happened. She always comes back.”

That night Hattie and Sam stayed up drinking coffee and playing poker.

“How’d you end up out here?”

“My parents were Paiute. Farmers. When they died I found Helen. That was a long time ago.”

“What about Helen?”

“Came from somewheres south. Don’t talk about it. Proved on this homestead–added to it. Me, Jack n Bill. Six hundred forty acres. Your turn.” She meant cards.

“I grew up in St Louis. Studied business and law. Seems like another lifetime ago.”

On those occasions darkness crept over Helen, cattle with brands that didn’t belong to her were found wandering her property. Sam worried the law would visit. After two years with Helen, giving his name as Sam Hall, he got a job with Miller and Lux. The work suited him. Quiet crept in and filled the crevices of his heart where the ache had been. Some nights around the campfire he felt like an old buckaroo like any of the men he worked with. He picked up his quill again and wrote poems about the desert and the vaqueros. And then the letter from Beryl arrived. His sister needed his help.

New Mexico Mystery

The wind blew through the weathered boards of the shack. In the morning Jack combed grains of sand out of his beard. May went around shaking out bedding and sweeping the floor before she’d start cooking breakfast–re-heated rabbit stew and biscuits. Jack sat out on the little porch, drinking coffee. His routine was to watch the sunrise over the desert. They had come by wagon in 1905, driven out of Texas by tornados. When he laid eyes on this place he knew he never wanted to leave. He didn’t consider the land for farming or ranching. Not a practical man, he simply liked the beauty of it. Proving on their homestead nearly killed the both of them. They weren’t young and this was a harsh country. Once they proved up, Jack scraped by hunting rabbits and the occasional deer. May helped on the Smith ranch nearby, cooking, cleaning, a little sewing. She was paid in milk, butter, flour, eggs, produce–whatever was available. They got by and were happy.